Follow the Data Podcast: Slowing the Spread of COVID-19 in Africa

A global pandemic like the coronavirus warrants an urgent global response. Though experts are still learning what makes the spread of coronavirus so viral, millions of lives depend on getting that response right – as does the economic and mental health of communities around the world.

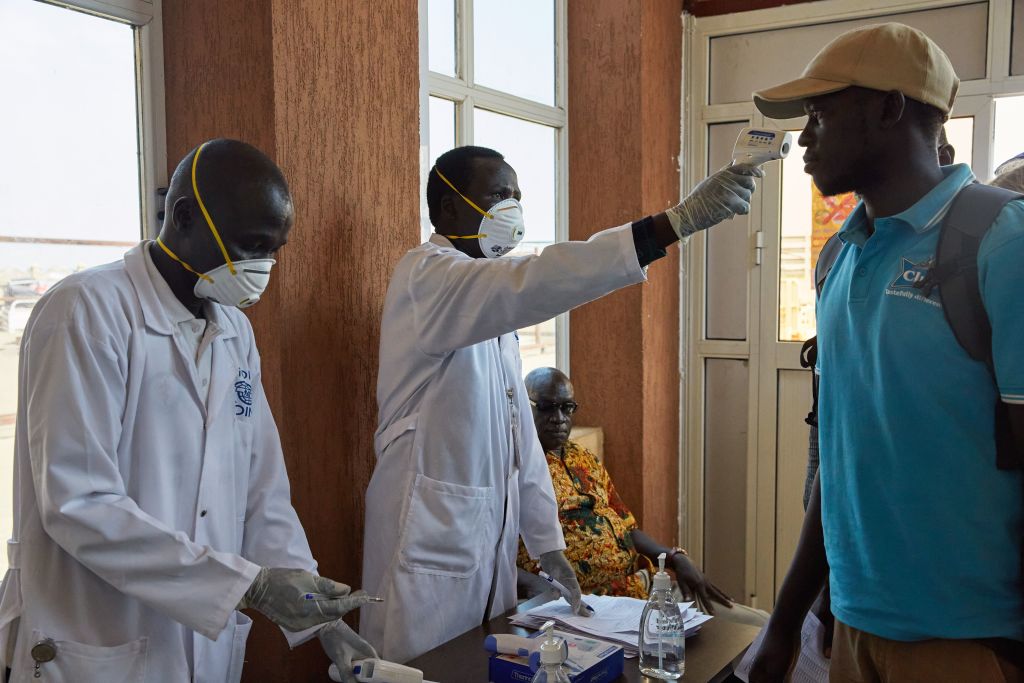

In Africa, where governments and populations are used to – or at least more aware of – highly infectious diseases from Ebola and other outbreaks, 36 out of 54 countries currently have social distancing measures in place. Yet caseloads are beginning to increase, and public health professionals are following the data to understand the severity and speed of the spread in Africa.

That’s why Bloomberg Philanthropies is partnering with global health organization Vital Strategies on global response efforts, along with the World Health Organization, to support immediate action to prevent or slow the spread of COVID-19 in vulnerable low and middle-income countries, particularly those in Africa.

In this episode of our series around Bloomberg Philanthropies’ COVID-19 response, Amanda McClelland, the Senior Vice President of Prevent Epidemics and Resolve to Save Lives at Vital Strategies, sat down with Dr. Jennifer Ellis, who works on our Public Health program.

They discuss why it’s important to prioritize slowing the spread of coronavirus in low- and middle-income countries, particularly those in Africa, the importance of the Box It In strategy, how response to the coronavirus has differed from other recent outbreaks, and what’s keeping public health professionals hopeful right now.

You can listen to the podcast and past episodes in the following ways:

- Stream it on SoundCloud.

- Check us out on Spotify.

- Download the episode from Apple Podcasts and be sure to subscribe.

- Listen to us on Stitcher – be sure to rate and review each episode!

- Tune in on Simplecast.

From more from our coronavirus series on our podcast:

On our most recent episode, “The Cost of Recovery for Our Cities, Part 1,” Adam Freed, a Principal at Bloomberg Associates, joined Natasha Rogers, the Chief Operating Officer of the City of Newark, and Brad Gair, a Principal with Witt O’Brien’s, a national emergency management consultancy, for the first episode in a two-part series around how cities can best navigate, access, and deploy federal aid.

Janette Sadik-Khan, a Principal at Bloomberg Associates, sat down with Corinne Kisner, Executive Director of NACTO, and Mark de la Vergne, the Chief of Mobility Innovation for the City of Detroit, to discuss the challenges coronavirus poses for city transportation departments and how cities are continuing to run transit systems while keeping their own staffs safe in “The Intersection of COVID-19 and Transportation.”

Dr. Josh Sharfstein, Vice Dean for Public Health Practice and Community Engagement at the Johns Hopkins School of Public Health, joined Beth Blauer, Executive Director of Centers for Civic Impact at Johns Hopkins, to discuss how the global COVID-19 tracking dashboard was made, what new features have been added, and how data can help individuals and officials make informed decisions for COVID-19 response in “Behind the Scenes of the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Map.” This episode was adapted from “Public Health on Call,” a new podcast from the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

Dr. Sharfstein sat down with Dr. Jessica Leighton, who works on our Public Health program, to discuss crisis response for public health practice and what makes COVID-19 different from other recent outbreaks in “Responding to a Pandemic Crisis.”

In “How to Help Nonprofits Hit Hard by COVID-19,” Darren Walker, president of the Ford Foundation, an international social justice philanthropy and one of Bloomberg Philanthropies’ co-funders in the NYC COVID-19 Response & Impact Fund, discussed how the coronavirus pandemic is affecting social services and cultural organizations in New York and the role of foundations in supporting those groups with Megan Sheekey, who leads our Strategic Partnership work at Bloomberg Associates.

In the first episode of our coronavirus series, “World War C- Us Against the Microbe,” Dr. Tom Frieden, the President and CEO of Resolve to Save Lives, and the former director of the CDC, discussed the global response to COVID-19 with Dr. Kelly Henning, who leads the Public Health program at Bloomberg Philanthropies.

Read the full transcript of this week’s episode:

Katherine Oliver:

Welcome to Follow the Data. I’m your host Katherine Oliver. A global pandemic like the Coronavirus warrants an urgent global response. Though experts are still learning what makes the spread of Coronavirus so viral, millions of lives depend on getting that response right, as does the economic and mental health of communities around the world. As mayor, Mike Bloomberg led New York City through public health crises, such as the swine flu outbreak in 2009, and the West Nile virus in 2012. His experience taught him giving public health professionals the tools and support they need to protect the public is essential to saving lives. That’s why Bloomberg Philanthropies is partnering with global health organization Vital Strategies on global response efforts, along with the World Health Organization to support immediate action to prevent or slow the spread of Covid-19 in vulnerable, low and middle income countries, particularly those in Africa.

In this episode of our series around Bloomberg Philanthropies Covid-19 response, Amanda McClelland, the Senior Vice President of Prevent Epidemics at Resolve to Save Lives at Vital Strategies sat down with Dr. Jen Ellis who works on our public health program. They discuss why it’s important to prioritize slowing the spread of Coronavirus in low and middle income countries, particularly those in Africa, the importance of the box it in strategy, how response to the Coronavirus has differed from other recent outbreaks, and what’s keeping public health professionals hopeful right now.

Jen Ellis:

I’m really pleased today to welcome Amanda McClellan, Senior Vice President of Epidemics at Resolve to Save Lives at Vital Strategies. Amanda, thank you so much for joining us today. I don’t think our audience has met you before, so would you mind starting just by telling us a little bit about your background?

Amanda McClelland:

Yeah, sure. And thanks so much for having me. In case you can’t tell, I’m Australian with a heavy accent living here now in New York, as you said working for Resolve to Save Lives, but my background is actually as a pediatric nurse starting off in Australia and I’ve been working humanitarian response mainly in conflicts and large disasters for the best part of the last 17 years and I’ve been really focused on epidemics and preventing epidemics for the last seven of those. So I’ve spent a lot of time in the field and dealing with the day to day of these emergencies. Now I’m based in New York working to support countries to better prepare and respond to outbreaks.

Jen Ellis:

We’ve been underway just over a month now and I know that our work together is really focusing on preventing or slowing the spread of COVID-19 in vulnerable, low and middle income countries. Can you talk a little bit about why it’s important for us to be focusing in the low and middle income country setting?

Amanda McClelland:

Although the COVID-19 threat is similar across the whole world now, it’s going to affect different populations in different ways and there’s probably two main ways that’ll happen. One will be the lockdown measures and the physical distancing measures are going to affect low income and vulnerable populations much more so than perhaps people that have the ability to work from home or have larger reserves in terms of savings and access to funding. So the way that we stop and slow COVID is going to impact low income countries much, much harder. But also the health systems that they have to respond to the outbreak are much weaker. Some countries that we’re working with have less than 10 ICU beds. And you would have heard, especially here in the United States, how many ventilators do we need, how much ICU capacity do we have? Well, some of the countries that we’ve worked with don’t have oxygen outside of the main hospitals and have less than a handful of ICU beds. And so this will impact low and middle income countries in a very different way.

Jen Ellis:

So our focus together has been primarily in Africa. You alluded to a little of this in your remarks just now about the health systems. Can you just tell us a little bit about what’s going on in Africa specifically? What does the outbreak look like there and how has the approach that you’ve designed really tailored to that specific setting?

Amanda McClelland:

The key piece for us is that we’re still learning every day, not just about the disease and the treatments and developing the vaccines, but what it looks like in different populations. And we haven’t seen the big, what we call exponential growth, those big spikes in cases that we’ve seen in New York and Italy and other countries. And we’re still trying to understand why we’re not seeing that in Africa. Is it because we’re not testing enough? Is it because it’s moving differently in a much younger population? The average age in Sierra Leone is 19.4 years. And so what does the outbreak look in a much younger population as opposed to Italy where there was a very large percentage of older people. Right now, it looks like Africa responded very quickly. Many of the countries implemented the physical distancing measures before they even got cases. Thirty-six out of the 54 countries currently have fairly strong physical distancing measures in place. And this is in part because they learned the lessons the hard way from Ebola and from other infectious diseases. The governance and the populations are used to or at least more aware of these highly infectious diseases and governments responded very quickly and did the types of things that we encourage countries to do early, which is contact tracing and following up passengers that came through the airport, communicating early about risk. What we are seeing we think is a delay in the introduction in Africa, but we are starting to see caseloads pick up. We were on the phone with Nigeria today. They’ve just had another hundred cases in a rural area start to kick off. South Africa is now over 4000 cases. Cameroon is also starting to get a lot of cases. They responded early and they responded strongly. But we’re still really looking at the data to see what it’s going to look like in terms of severity and speed in Africa.

Jen Ellis:

I’m interested in what you just said about not knowing really enough about the pandemic there because of the lack of testing. Are you also seeing a lower number of deaths than you would expect at this point in a pandemic if the growth curve were looking like it has looked in other countries like Italy and the US that you mentioned?

Amanda McClelland:

Deaths are probably one of the easiest indicators at the beginning and in a crude way to explain it’s easier to count people that have died than people that are sick, especially with something like pneumonia that can get really mixed in with a lot of other diseases. In terms of the numbers of deaths, it’s looking similar to the case fatality rates that we’re seeing in other countries, especially at the beginning of the outbreak. So it’s still sitting at around that 3-4% but it’s also for the same reasons that we’re seeing in other countries, which is we’re most likely just detecting those very severe cases. We’re probably not picking up that asymptomatic or mild transmission that we know makes up about 80% of the caseload so far.

Jen Ellis:

You referenced the Ebola outbreak a minute or two ago and especially with respect to how much planning these countries have had to do because of the Ebola outbreak. Can you tell us a little bit about how the response to Coronavirus in Africa has been different or similar to what you saw in the Ebola outbreak?

Amanda McClelland:

There’s a lot of similarities in terms of the response strategies for Ebola, but they’re also very, very different. So Ebola is extremely severe without treatment. We see 70% of people that catch Ebola die or pass away in comparison to COVID where we’re looking at 1-3%. So the severity of Ebola is obviously much, much higher, but it’s not as transmissible. So it doesn’t spread in the same way that COVID spreads via the air. You have to touch people and you have to come into contact with people and so it is somewhat easier to slow down the spread of Ebola if the community is able to adapt their behavior.

But there’s a lot of things. The core public health skills that we talk about in Resolve about boxing it in really are key to both diseases. Box it in is a core strategy to public health. It really means that we need four things to all work together to reduce the virus transmission load or how many people are sick. The first part of that is identifying people that are sick. So being able to test and verify that people have COVID. The next part is about contact tracing people that they may have come into contact with. So understanding who may have been exposed to the virus and getting a list of those contacts. And then the third piece is isolating those people, making sure that they stay inside for the 14 days so that just in case they did get sick, they’re not spreading it to other people. And then if they do get sick while they’re in isolation, making sure that they get access to care. And so those four things together are what we call test, track, trace and treat help us box in the virus and reduce the number of people that are transmitting it. So there’s core public health skills that really helped countries get on top of Ebola and get to zero are really the same skills that we’re using to track and to isolate cases for COVID. And so we’ve seen countries respond very well. They have the contact tracing teams ready. They have them trained. Ebola has been in DRC, in the Democratic Republic of Congo, for the last 18 months. And so many of the countries surrounding DRC have been on high alert for several months now waiting, watching for cases to come across the border. And so that higher alertness and readiness of those countries has really benefited them in responding to COVID. But they use these same skills for other diseases. Initially HIV back in the 1980s and 1990s, same similar method trying to track and follow up cases, contact trace people that potentially have come into contact with HIV and we use the same strategy for tuberculosis and the same strategy for polio. What will happen is that they will run out of resources quickly. So they’ll be overwhelmed by the volume of COVID cases potentially. And so support like we have from Bloomberg and the technical support from Resolve to Save Lives is critical in helping scale. Everything will be about scale now that we’re in a pandemic. And so it’s really about strengthening those systems, providing funding and training and support to scale them up to ensure that that good work they’ve been able to do early can continue to match the need as cases start to spread.

Jen Ellis:

So, Amanda, we’ve been underway about a month, a little bit longer. Maybe tell us a little bit about what it’s been like over this first month or so and how the program has been running, what your areas of focus have been.

Amanda McClelland:

The focus has really been getting countries ready and getting support out as quickly as we can. And so in collaboration with Bloomberg, we really focused on meeting those immediate needs for countries.

This really rapid access to money and to support allows countries to keep caseloads low and to stop the spread. And so it feels sometimes a little bit silly but sometimes the biggest barrier to getting work done in parts of Africa is not having fuel in the Land Cruiser and you have to get four pieces of paper signed to get a tank of fuel. That type of support has been able to cut those timelines down and to stop those obstacles that sometimes feel a little bit silly or a lower priority during an outbreak in being able to get people out there.

The other thing that we really focused on is risk communications. Helping governments clearly explain this new disease, explaining the risk and advocating and working with them to adapt their behaviors.

The other thing we really focused on the beginning is training frontline healthcare workers and this really goes back to being a nurse and prioritizing those people on the frontline but also from working in the beginning of Ebola in one of the hospitals I worked in and set up, we lost 54 nurses in just two weeks to Ebola. And so really learning that lesson, that the PPE that you hear so much about that on the news is very hard to get in Africa in the best of times. Most primary health care clinics don’t have access to even water or power and so we really prioritize getting down to those frontline healthcare workers, helping them understand what the risks are and adjusting the way that they work to reduce their risk of getting COVID, really protecting that frontline worker system, not just from COVID but to ensure that they’re able to carry out the rest of their essential work and that we prevent things like decreasing vaccination rates and increase in malaria. So really important work in terms of maintaining health services there.

Jen Ellis:

Wow. It’s hard not to respond to your comment about the need to protect frontline healthcare workers and especially some of your experience in Ebola. Have you been able, even in this very short time that seems like a very long time, to actually have the protective equipment reach the frontline healthcare workers already?

Amanda McClelland:

So we’ve had to find other ways to meet that need. So being able to get enough personal protective equipment all the way down is a challenge. Even at global level, there’s what we call breaks in the pipeline and we’re not able to access large amounts of material. So what we’ve been able to do is to work with local partners and the clinics themselves to improve what we call administrative and environmental controls. These are simple things like making sure that they’re first checking patients outside in open areas to decrease risk and separating out patients that might have COVID from patients that don’t, making sure that we’re triaging and quarantining, increasing ventilation, but we’ve also been doing things like making alcohol hand rub. If we can’t get water into each clinic, we can at least get hand sanitizer. It’s very easy to make at a local level and one of the clinics in Uganda last week made 1200 liters. It’s very cheap and very easy to make but makes a big difference at the clinical level.

And then we’ve also found it’s very easy to make face shields locally. And so we’ve been working with partners to buy laser cutters and to develop and to cut the plastic needed for face shields at the local level. So a lot of this requires some innovation and adaption, but these clinics and frontline healthcare workers are used to working in those types of conditions and with a little bit of support and the right information they’ve definitely been able to improve the situation there.

Jen Ellis:

Wow. Incredible that you can be that adaptive and that the countries can be that adaptive even in such a challenging time. What are the things that have surprised you the most over the past month or so as you’ve undertaken this work?

Amanda McClelland:

I think the thing that surprises me most, I guess it’s just the volume of information about what we don’t know around the disease and how quickly we’re having to synthesize the information and adapt it to strategy. But I have to say I’m quietly impressed that all the work that we’ve been doing and the partners that we have on the ground have responded so quickly and effectively to the risk of COVID and we’ve seen some delays in other countries not necessarily as used to working infectious diseases and we haven’t seen that in Africa. We’ve seen politicians and senior health ministers lean forward into COVID risks, really take it very seriously early on and really try to do their best to prevent the spread knowing that if a large scale spread happens in their countries, the impact could be devastating.

So I’m continually surprised at the resilience of the teams on the ground and their determination to work to protect their communities and it continues to motivate us to keep working hard.

Jen Ellis:

I know that you’ve found out some really interesting information about how African countries can adapt to the social measures that are being recommended while still making sure that they’re taking care of their populations. Can you talk just a little bit about some of the things that are specific to the African setting that you’re recommending when you’re giving technical assistance about how to do social distancing in that setting?

Amanda McClelland:

I mean I think it goes back to the point when we meant that when you’re in lower resource settings you’re continually adapting and changing to make the most of what you have and the situation that you have and that’s true also for physical distancing measures. And so early on we realized that the recommendations that we were seeing coming out of even China and Korea and the US were going to be very difficult to adapt in low resource settings. It’s easy to say wash your hands every time you touch something, but if you don’t have water or soap available, it’s very difficult to implement. We talk about physical distancing, but a lot of people live in informal settlements, in very crowded houses, sometimes one room with multiple people inside. So things like isolating when you’re unwell are very difficult. Things like stay at home from work when you’re sick is very difficult when you don’t have any access to sick leave or you only get paid for the hours or the work that you do.

So many of the problems that we see in developed countries but at a much bigger scale and more difficult to implement. What we’ve been very pleased about is we just finished a survey in 20 countries to assess communities’ understanding of COVID but also their willingness to implement the physical distancing measures. When we did the survey, we picked four countries from each of the four regions to be representative of the whole of Africa. So it’s rare that we actually mean the whole of Africa when we say that, but in this case we do. And what was really great to see is 90-97% of the community know what COVID is and understand it, which is amazing. When we worked in Ebola, sometimes that number was as low as 20% so the people in Africa, the governments, have done a great job of getting the news out, getting the information out. People know what this disease is, they know what it can do and they are very supportive of the physical distancing measures. There’s very high support for stopping schooling, stopping mass gatherings, even stopping soccer which I was surprised about, stopping football.

But what people were concerned about is that they only have a week supply of food or a week supply of money. So if they have to stop movement completely, within a week they would really be in a difficult position. And I think the other big piece was only 40% of people had an additional room where they could isolate someone. And so we are working with governments now to adapt those measures, making markets safer so that they can keep them open and people can go regularly. Looking at things like shielding or keeping our older, more vulnerable people separated from the rest of the family. And so we call it house swapping, putting some of the older people or the people with co-morbidities in one house and moving all of the young people to separate houses to stop the exposure between the two groups. And so we’ll continue to work in but we have seen some really practical innovation at country level to try to make sure that the physical distancing measures work in those contexts.

Jen Ellis:

Wow. Well there are so many more things I think we could ask you about and I know we’re going to look forward to hearing more. I think I’d love to end by hearing a little bit about what has given you hope as you’ve worked on this over the last a month or so and what’s really keeping you hopeful about what the next few phases of this look like?

Amanda McClelland:

I think the global solidarity as someone who used to work in behavior change full time to see the whole globe coming together really in this social solidarity, staying at home to look after one another has really given me hope that we’re only going to beat this really by behavior change until we get access to a vaccine and to effective treatment. It’s going to be how people behave and how we all adapt to the new circumstances that’s going to make a difference and it’s been overwhelmingly impressive at at how people have come together to support one another and to understand it’s not just about them, but it’s about the neighbor next door and their community. And so that’s what’s given me hope and we understand that it’s hard and we understand people want to come out and we understand things want to get back open and I think as a public health team we’re working as hard as we can to make it as safe as we can for people to come back out so to speak. But hoping that people can maintain that level of adherence and compliance and working together until we can make it safer.

Jen Ellis:

Great. Well thank you and thank you to everyone at Vital Strategies for everything you’ve done to do such impactful work so quickly. We’re really glad to partner with you and thanks for joining us today.

Amanda McClelland:

Thanks.

Katherine Oliver:

We hope you enjoyed this episode of Follow the Data. Many thanks to Dr. Jen Ellis and Amanda McClelland for joining us. If you haven’t already, be sure to subscribe to Follow the Data Podcast and tell your friends to subscribe as well. This episode was created by Devin Alessio, Ivy Li, Amie Juhn, and Eliot Popko. As our founder Mike Bloomberg says, “If you can’t measure it, you can’t manage it.” So until next time, keep following the data. I’m Katherine Oliver, thanks for listening.